The Pedagogy of Matthew Fox

In establishing his master's program in Culture and Creation Spirituality beginning in 1978 at Mundelein College in Chicago, and reaching its zenith in the University of Creation Spirtuality in Oakland, CA, Fox consciously and deliberately stepped out of a European and modern model of education, one that defines truth as "clear and distinct ideas" (Descartes) and therefore as left brain or rationality exclusively. Instead, he introduced "art as meditation" and body prayer as essential parts of the learning process, thus bringing in the right brain or intuition/mysticism for balance as well as the body. This pedagogy instructs all seven chakras. Over 35 years of teaching adults and more recently adolescents, results have demonstrated the usefulness of this holistic educational model. More can be found in Fox's autobiography, Confessions: The Making of a Post-Denominational Priest.

The impact of this pedagogy has gone far beyond the lives of its students: its graduates have gone on to make a profound mark upon the world. Among them are Bernard Amandi, who started Engineers Without Borders and later co-founded Engineers Without Borders-International....Mel Duncan, who started the Nonviolent Peace Force, professionally training civilian peacekeeping forces around the world....bestselling author/medical intuitive Caroline Myss...and Sister Dorothy Stang, who was martyred in Brazil for standing up for the preservation of the Amazonian rain forest and the rights of rural farm workers.

The 10 Principles of Wisdom Education

Out of those years of teaching graduate programs, Matthew Fox distilled 10 radical principles of Wisdom Education, which he later implemented in the Youth and Elders Learning Laboratory for Ancestral Wisdom Education (YELLAWE), a program for urban youth in the public schools of Oakland, CA.

While UCS has been subsumed in its successor, Wisdom University, and YELLAWE closed in 2016, the principles of Wisdom Education have since been adapted and extended by UCS graduate and YELLAWE director Theodore Richards in the Chicago Wisdom Project. They are now being re-visioned by UCS graduates in a new graduate/postgraduate program, the Fox Institute, slated to open in 2017.

The 10 principles described below have been drawn from Matthew Fox's book The A.W.E. Project: Reinventing Education, Reinventing the Human.

(1) Cosmology & Ecology (p.104):

The human body is not separate from the world, but part of an interconnected community of beings. The chakra system, as in many cultures, shows the human body as a microcosm of the Universe. (The Seven Chakras are paralleled by the seven cosmic spheres). While both cosmology and ecology will be studied extensively, students should understand some basic definitions:

- Ecology comes from the Greek “Oikos” meaning “home.” It refers to the living community that is our true home.

- Cosmology comes from the Greek “Cosmos” meaning both “beauty” and “order.” It refers to the study of the Universe and how we can find a meaningful and unique place in it. Cosmology is how we see our connections to one another and the world.

(2) Contemplation (p.108):

Students should understand the basic meaning and purpose of contemplation and meditation, as well as the philosophy and cosmology underpinning the practice.

- What does contemplation mean? ("Contemplation is the highest expression of man’s intellectual and spiritual life. It is that life itself, fully awake, fully active, fully aware that it is alive. It is spiritual wonder. It is spontaneous awe at the sacredness of life, of being. It is gratitude for life, for awareness and for being." - Thomas Merton)

- Basic Philosophy of Yoga practice (seven chakras [p.141] and eight limbs)

(3) Character and Chakra Development (p.138):

In order to see the interconnectedness, the contemplative practice should move right into a discussion of Character. Contemplative practice serves not only to find inner peace, but to cultivate one’s character in facing the world. What are the attributes that make up a person’s character? Use a diagram of the human with the seven chakras. Begin with the students’ ideas about what constitutes a whole person and good character. From that list, place appropriate ideas on the diagram and describe the attributes of each chakra. (p.141)

(4) Creativity (p.111):

Students should understand that the third phase of the program is creative, and that they are expected to create something based upon the class. In addition, students should recognize how the Wisdom Education pedagogy is different in its emphasis on the student’s creativity. Instead of being given information to learn, the students become teachers as they integrate lessons and experiences and express them in their own, unique way. It is also helpful to ask the students what creative talents and interests they bring to the program.

(5) Chaos & Darkness (p.115):

Chaos provides the balance for Cosmos. Students should recognize the difference between opposites (e.g., good and evil) and the dynamic tension of concepts like chaos and cosmos (or yin and yang, which is particularly important if students are using a contemplative practice based on the Chinese system). It refers to “disorder” now, but comes from a Greek word meaning “void” or emptiness. At this point, students should become familiar with both of these definitions. To begin with, ask the students what associations they make with chaos and darkness. If students come up with negative associations, encourage them to begin to think of how they can be seen positively.

(6) Compassion (p.121):

Students should understand the meaning of compassion. It literally means “to feel with” (Latin com=with/pathos=feel). This is different from feeling sorry for someone or even to do what one thinks is fair. An emphasis can be placed how compassion is linked with a mother’s care for a child. Students are encouraged to see how they can live their lives more compassionately.

(7) Community (p.130):

In many ways, one’s capacity for compassion has to do with how community is defined. At this stage, the students should simply define what their community is. Students should be encouraged to think of community in ways that move beyond physical proximity.

(8) Critical Consciousness & Judgment (p.126):

What does it mean to think critically? When we are given information, do we always accept it? Whom do we trust? Friends? Parents? Peers?

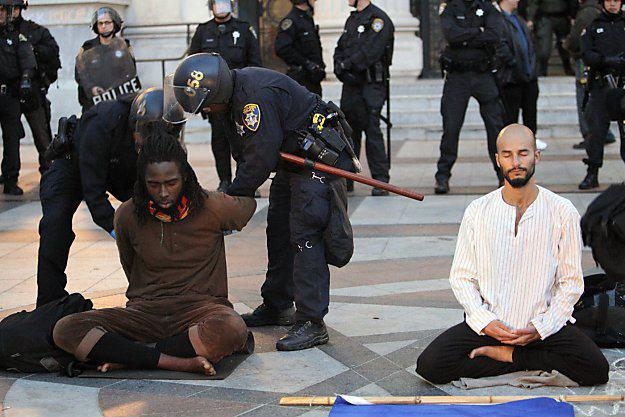

(8) Courage: “Compassion is not possible if we lack courage” (p.124).

And our Critical Consciousness doesn’t do us much good without courage, either. Ask the students for examples of courageous people.

(10) Ceremony, Celebration, & Ritual (p.136): Questions for discussion:

- What rituals do you have in your lives?

- Why is ritual important for people of every culture and how does it build community?

- What happens to a society that has lost its rituals? An example: gang initiations that have arisen in the absence of traditional rites of passage.

Note that the students will have a ceremony as a way to share with the community and integrate what they have learned.